The other week, my husband wanted to take me on a date to the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI). He told me not to look up the main exhibit because he wanted it to be a surprise. “Let’s get lightly stoned,” he said. I was certain I would be able to appreciate whatever was in store while sober, but because we had both been so melancholy in the wake of losing our beloved cat to cancer, getting a little giggly sounded nice.

I bought the weed gummies. We ate them. What you need to know is that I don’t normally “do” weed and I’m not great at math. The finer details—of how we went from wanting to “get lightly stoned” to each of us consuming 25mg of THC—aren’t important. Long story short: we got very, very stoned. We blasted off.

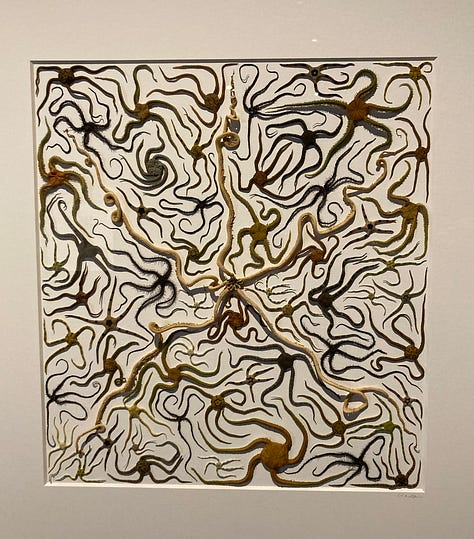

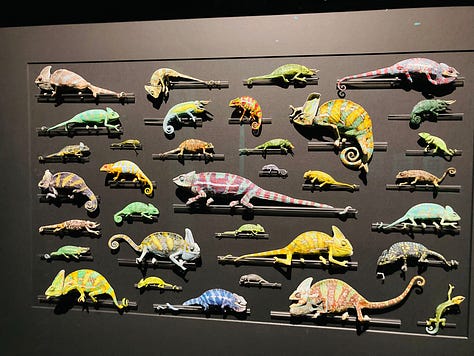

We went to the museum. I still thought I would have appreciated Christopher Marley’s “Exquisite Creatures Revealed” while sober, but the weed allowed me to lean into a mesmeric state. I could lose myself in the hypnotic patterns of butterflies arranged in iridescent whorls and Escher-style tessellations. I delighted in the fancy outfits of the decorator crabs. I stood, mouth agape, in front of striped urchins and beetles and snakes, aching to account for the ornate design of each formerly living being.

Through collaborations with zoos, museums, aquariums, fisherfolk, and indigenous tribes, Marley ethically collects vertebrates, invertebrates, and plants from around the world. He then preserves and arranges them in artful patterns aimed to provoke. Some of the specimens seem otherworldly—Japanese spider crabs large enough to hug Honda Civics, seadragons that resemble plants—and then one remembers that these creatures exist in our world. And that’s what makes the exhibit so exquisitely astonishing and so unbearably sad.

Maybe it was the weed or maybe it was the stirring music playing overhead, but as I drifted from specimen to specimen, marveling at each masterpiece of evolution, my mind sank into reflections on deep time. How heartbreaking, I thought, that humans are causing the extinction of creatures that have evolved over billions of years to look this gorgeous, to adapt to their habitats this functionally, to fill such specific roles in the intricate, interlocking web of biodiversity.

Teary-eyed, I began to see the exhibit as the most important thing that had ever happened in the history of humankind (I admit maybe this was the weed talking). I was confused about why this exhibit wasn’t making headline news. Why aren’t all the people in the world here right now to witness this?, I wondered. Where is everyone? A panicked, evangelistic urgency spread through me. I decided that when we got home, I would write about what I’d seen. I would shout about this from the rooftops. However, when we made it back to the comfort of our couch, all we managed to do for the next four hours was order pizza and binge episodes of How I Met Your Mother.

Even though the weed has long worn off, I continue to feel affected by what we saw that night. Admittedly, the experience was more morbid than going to the zoo; these creatures are not animate, their bodies stiffened by death and lacquer. And maybe that’s why their lives hit me so hard. Never again would these individuals crawl, slither, fly, or swim across this planet. When you extrapolate this loss out to an entire species, the repercussions feel catastrophic. Even without knowing all the ways a species is vital to the healthy functioning of an ecosystem, when face to face with singularity, it’s hard to question something’s value. It is one thing to know that the corpse lily is at risk of extinction. It’s another to stare into its spiked gullet and let one’s eyes digest the sheer size of this spotted, brown behemoth, which can grow up to four feet in diameter and weigh as much as the average store-bought watermelon. It blooms once every four to 20 years and lasts for about five days. It smells strongly of rotting flesh.

Why does such a plant exist? Do we need to know, or can we simply appreciate that it does and revere it for its weirdness?

We’ve all heard the word “biodiversity” so many times that it has lost some of its meaning. “Exquisite Creatures Revealed” challenges our apathy by situating, side by side, different species within the same taxonomic order. What this does for the viewer is turn a category—such as “turtle” or “sea urchin” or “beetle”—into a dizzying array of variation. The world is striped and spotted, fringed and forked, diaphanous and dazzling. Neon is no longer the stuff of raves and highlighter pens, but a phenomenon of feathers and scales. The finest jewelry in the world cannot out-glitter certain bugs.

On one of the art plaques, Marley muses about why humans value diamonds so highly. “While they do have limited industrial uses,” he writes, “diamonds are dramatically less essential to humanity than scores of other materials and organisms.” He admits that the adjacent piece, comprised of 165 carats of raw diamonds arranged together, was one of the more expensive works to produce, “yet will likely be the most unremarkable thing you will see today.” So why all the fuss about sparkly stones? “There is an important lesson here,” he writes. “We prize diamonds primarily because others do—and perhaps this is a tendency we should reconsider.”

Marley urges us to pay attention to which specimens in the exhibit we feel most drawn to. “These are your jewels,” he writes, “and nature beckons uniquely to each of us through them.”

For Marley, nature beckons most irresistibly through snakes and insects. Growing up, he was a self-proclaimed reptile freak, always combing the forest for lizards and snakes. He wasn’t as fond of bugs, though. Then came a trip to Taiwan where he took time to notice how gorgeous insects could be. Now, he lovingly calls them “perfect little monsters.”

The bugs were one of my favorite parts of the exhibit. The colorful arrangements are breathtaking, more beautiful than anything I’ve seen in a jewelry store. No matter how long I stood and stared at the sparkling rainbow array, my eyes could not take it all in.

Last week, The New York Times Magazine published an article by Meg Bernhard about two activists who are fighting to preserve the biodiversity of Nevada’s deserts, a place many climate experts see as a valuable resource in our country’s green energy future. In “The Land of Hard Choices,” Bernhard deftly writes about the opposing viewpoints. On one side, you have activists who want to protect species like the rare Amargosa niterwort, an endangered plant endemic to the Amargosa Basin. On the other side, you have climate experts who want to push lithium mining so the U.S. can be less dependent on other countries in the race to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Both endeavors are important, but is there one we should value more?

The Amargosa niterwort is beautiful. This plump green succulent produces pink petallike sepals that are a dusky rose color. I hadn’t known the plant existed before reading Bernhard’s article. Now, I’m trying to imagine a world in which it no longer exists.

“How do you absorb it?” said one of Bernhard’s sources during a visit to the Amargosa Basin, referring to the desert’s blooms, scents, and colors. “You never know when you’ll see it again.”

Reading that line, I realized that’s what I’d been trying to do at the exhibit. Take it all in. Absorb it into my bones. Bear witness in a way that could somehow honor the existence of such beauty, given that the existence of certain species may soon cease to be.

“Does finding beauty in nature make us more likely to cherish and protect it?” Marley asks.

A few days ago, I returned to the exhibit. Even without getting stoned, I still got teary eyed. I still felt the urge to tell everyone about the beauty I beheld. But this time was different for one important reason: I didn’t feel alone in my wonderment. The first visit, I’d been too absorbed in my own experience to pay attention to the people around me, and that had produced an isolating effect. My panic had arisen from a place of fear that few others would value the exhibit the way I had. What if other people looked at Marley’s “perfect little monsters” and saw only the monstrousness and none of the beauty?

This last visit, though, I watched a child approach a snake as thick as a human thigh until the scales were inches from her nose. I heard a small boy call one of the pieces a “swirl of turtles” and shriek with delight when he spotted the tiniest one in the center of the swirl, no bigger than an acorn.

“That is unbelievable,” said one man about the bugs.

“It’s just so pretty,” said a woman near him. “Every color you could possibly imagine.”

It was sobering to feel such kindred company with strangers. The shared amazement was potent. Our passion for these creatures seemed the unlikeliest of love stories, yet our human hearts were wild about these captivating corpses. It made me wonder: What might happen if we transferred this collective love to those that are still alive?

If you’re interested in seeing “Exquisite Creatures Revealed” for yourself, make haste! The exhibit ends on February 17. Get your tickets here.

Updates

An essay I wrote about getting married was recently published in the New York Times’s Modern Love column. I originally titled the piece “We Got Married for the Party.” The Times ran it online with the headline “A Marriage Starts to Unravel on the Honeymoon.” I prefer the print edition’s version of the headline: “Fortunately, the Honeymoon Period Came to an End.”

I was thrilled to see my Switchyard essay “How to Steal a Whale Bone” included in one of Memoir Land’s recent essay roundups. The essay is part heist, part reflection on what we think we own and why.

Needed this reminder to get myself to OMSI!